See you down the Pub!

A group of locals outside a Mitchell's and Butler's Pub probably in the West Midlands. Note the solitary woman - was she the landlady or barmaid?

The following short article of mine appeared in Local History Magazine (No 65) in 1998. It led to a lot of interest.

The public house has a unique role in British society. There can be few people who have never visited one. And for many, like the author, hour upon pleasurable hour has been spent in inns and taverns of all kinds. For local historians the public house, along with the street pattern and street names and the parish church, are part of a trinity of tangible evidence that link us in a very real way with the past. The Red Lion is still likely to be opposite the church on Church Street, even if Church Street is now a busy dual carriageway, the Red Lion a bare shadow of its former self, and the church itself derelict.

Even if the buildings themselves change, from Georgian coaching inn, through Victorian gin palace to Irish theme pub, the site is likely to have housed a public house for centuries. Brewers are traditional folk and don't like to change a successful formula. If a pub is popular with one generation it is likely to be popular with succeeding ones.

Careful examination of the outside of a tavern can often reveal signs of their history: two cottages or houses knocked into one, or a pub which has expanded into neighbouring houses or shops, windows carrying the name of a long defunct brewery (George IV, Portugal Street, London WC2) , or on rare occasions a brew house in the backyard (Lamp Tavern, High St, Dudley).

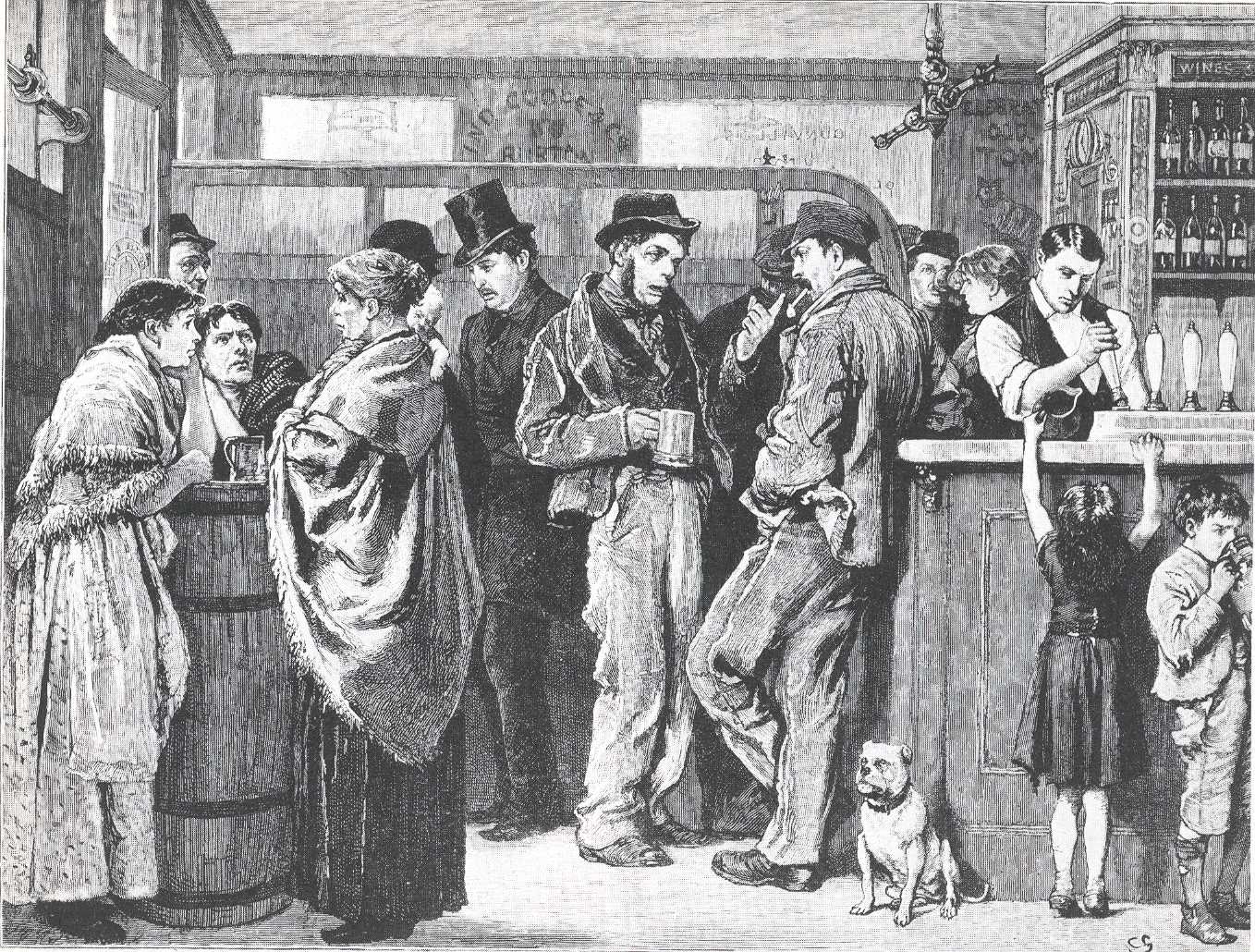

'A Saturday afternoon in a gin palace' Drawn from life for The Graphic, 1879

Except in a very few gems the inside of most pubs have been greatly altered over the years. It may however be possible to trace where smaller bars were knocked into one (Coach and Horses, Kew Green, Richmond), or expanded into rooms at the back (The Vine, Delph Road, Brierley Hill, West Midlands). A few unspoilt pubs remain, such as the rural Rising Sun, High Wych, Herts or the splendid Victorian Philharmonic, Hope St, Liverpool, were it is possible to get a real feel for what it must have been like having a pint a hundred or more years ago.

Many pubs have been lost over the past century or so. Some lost their licences at the turn of the century when an upsurge in temperance feeling coupled with concern over working class drunkenness saw the disappearance of many bars. In recent years the breweries have closed many uneconomic pubs. It is often fairly easy to spot when a building was formally a pub. Perhaps some tiling remains, or a door is in an odd place, or it was the slightly grander building at the end of a terraced street. Sometimes parts of a former inn lies preserved behind a more modern exterior. The Greyhound, George Street, Richmond for examples now forms part of an office block.

Some pubs have photographs of themselves on the walls. Many of the Weatherspoon chain of pubs display old photographs of the area on the walls, so a local historian can spend happy minutes studying the decorations, while being stared at by other customers.

There are regional variations in pub architecture. A Northern pub with a narrow corridor leading to a variety of small rooms is relatively uncommon down south. Two good examples of these pubs are the Grey Horse and Circus which are nearly next door to each other on Portland Street, Manchester. In southern England many pubs traditionally consisted of an entrance to two bars, a saloon and a public bar, with an off-sales point in the middle. Here very occasionally snob screens may survive where in days gone by a man might stand at the bar for a quiet drink without the embarrassment of being seen by his servant or indeed master (The Lamb, Lamb's Conduit Street, London WC2).

If you are interested in tracing the history of a local public house there are very sources which could help you. Pubs are often marked on old maps and appear in street directories so it is often possible to get a rough idea of when a tavern was first built. You should be aware that pubs sometimes change their name for quite inexplicable reasons, the Crown could become the Bull and Bush and vice versa. However it is only in recent years that a craze has grown up to give pubs stupid names (Scruffy Murphy's, Slug and Hedgehog etc etc). Readers will agree with me that this habit should be resisted where ever possible!

Public houses, and the activities associated with them, were the favourite subject of early photographers, so it should be possible to get a photograph of what the place liked a century or so ago.

Brewery records are often a good source, although their survival is a bit patchy. Some breweries keep their own records, but many have been deposited at local record offices. Young's, Bass, and Whitbreads in particular have their own archives. Their records are likely to be able to tell you from whom the pub was bought or when the land it was built on was acquired. There may be material about rebuilding or redecoration, with plans and architects' drawings. Deeds and other legal records may tell you who the tenants were, information which might be fleshed out by looking at nineteenth century census records.

County record offices may well have licensed victuallers' records. From 1552 alehouse keepers had to have permission of the local justices of the peace to sell beer. Records are often arranged by licensee rather than by the name of the public house. A guide to this material is Jeremy Gibson and Judith Hunter's Victuallers' Licenses (FFHS, 1997)

There are several histories of pubs and beer in Britain which can be found in many local libraries. Occasionally breweries have produced histories of their pubs. A particularly example is Helen Osborn's Inn and Around London: A History of Young's Pubs (London, 1991). Unfortunately there doesn't appear to be public house historical society. However if you are interested in brewing you should join the Brewery History Society. The Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA)'s Pub Preservation Group does an excellent job in stopping the worst efforts by brewers to ruin perfectly good alehouses. This is nothing new, people such as Osbert Lancaster and John Betjeman in the 1930s were deploring the same attitude towards the tied estate.

Whatever you care to call them, public houses, taverns, inns and alehouses all have a story to tell. As local historians we should be bringing out these tales, as well of course imbibing liquid history in their bars!

Copyright 2000. All rights reserved.